Paralingual Index no. 1

Index / typeface

The index can be downloaded for free here.

Please, use it with care. Let me know how it goes:

clara.sindal.mosconi (at) gmail.com

The following is a reedited chapter from my thesis Una Voce Adesso,

published in Malmö Art Academy’s Yearbook, 2023.

“My language doesn’t have a dominant language. Having many languages is like having many selves. My language often feels dispersed. She hesitates before she speaks.”

– Mirene Arsanios1My relationship with Italian behaves in an almost mythical way. To be perfectly honest, whether or not I ever spoke Italian isn’t entirely clear to me. As a child, bolstered with uncompromising self-confidence, I was convinced that I could speak the language. I can clearly remember how I demonstrated (performed) my Italian, in order to impress the other kids at school when, every autumn, I would return after spending another long summer in Italy. Convincingly, I rolled my r’s, coloured and conducted the pitch, and softened my double consonants. Perfetto. I wasn’t the least bit conscious about the well-orchestrated performance at that time, but I was absolutely certain about what my ears had heard, and I was the master of imitation.

As time went by and I got older, and generally more and more bashful, my “Italian” actually faded. The summers grew longer. I fell silent. And a growing shame about my lost language came to the fore. The fear of making a mistake sat inside me, and I wouldn’t hold a single Italian word in my mouth. My identity came to be embraced by a wordlessness, and things didn’t have any words: no language was connected to them. Instead, they were merely sounds emitted from the mouths of others. I perceived everything in a wordless state of being, in parallel with a language that I couldn’t attain on the same terms as could the rest of my Italian speaking family. Things were sounds, waves, particles. They were nameless, I was wordless.

And at the same time, language was as clear as water. I heard right through the words, without getting captured by metaphors and heavy meanings that were closely attached to what was being spoken. Instead, it was pure, sonic aesthetics. Sounds I had been listening to ever since I was a child. Sounds that had forms and colours: temperaments without literal meaning.

Systematising the Uncontrolled

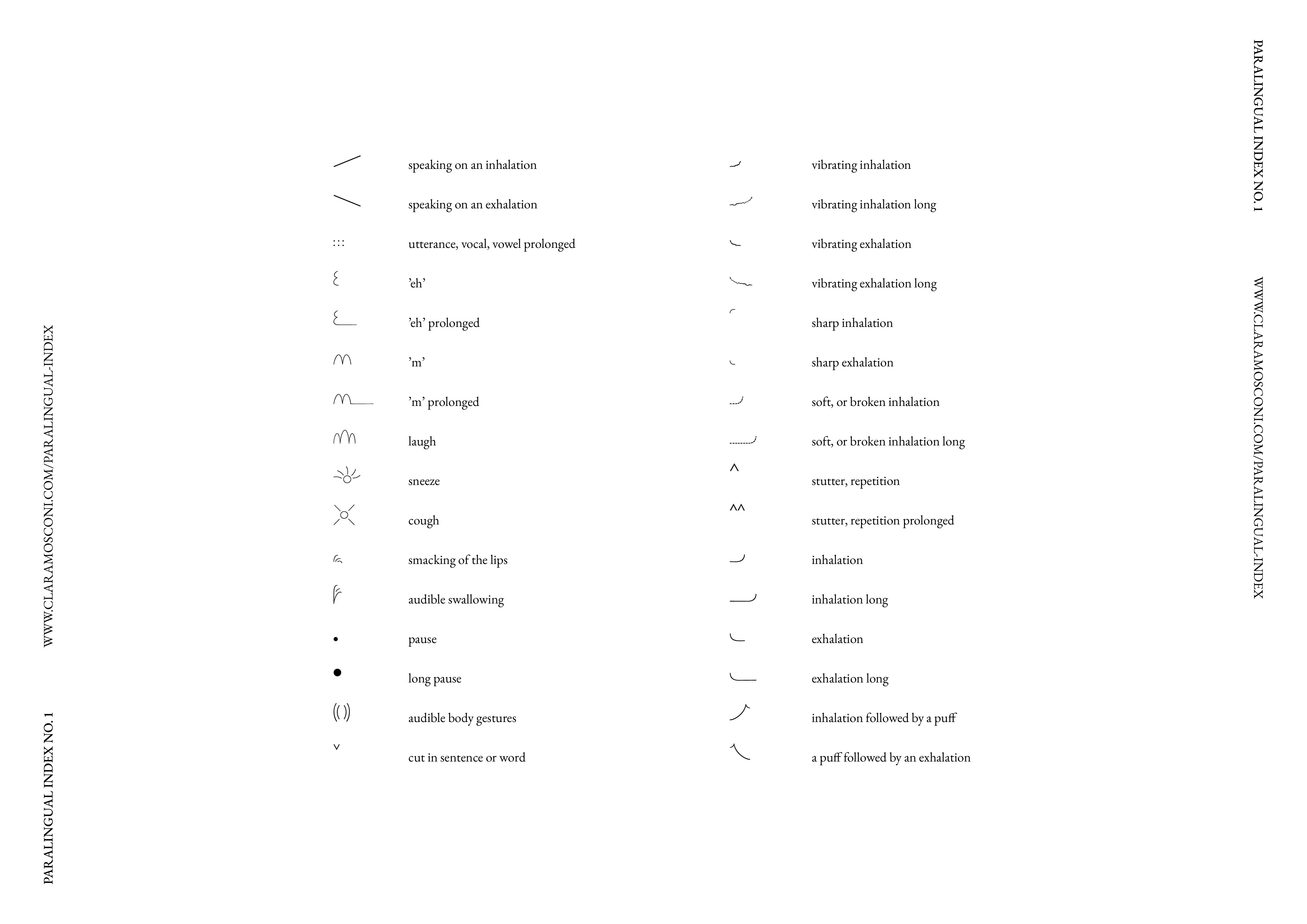

I have worked out a series of symbols that I call the “paralingual index.” These symbols mark the paralinguistic sounds in our language. The index is an implement that precisely transcribes the sounds that the voice automatically makes—the uncontrolled language for which we have no rules and systems. The symbols are intuitive in their design, and they refer to the sounds’ performative aspect, that is to say, to how the sounds relate to the body.

The index depends on sound. It doesn’t need any words, but the voice is essential. A transcription of the sounds thus describes, to a far greater extent, the person who is speaking than it does what is being said. For this reason, the transcription is always going to be personal and closely linked to the speaker, and maybe will also elicit an image of a state of mind, a human being, more than it will convey a message for interpretation.

The index is dependent on a conversational situation. It cannot be applied to a monologue or other rehearsed speech, as it touches on a certain kind of spontaneity: a dialogue between a speaker and a listener, by turns, a sender and a receiver: of blood, desires, and longings. And if we allow the sender and the receiver to speak two different languages, without sharing a second or third language, the conversation becomes dependent on everything but words, and the friction between the two languages becomes intensified.

It is inside that space that we are inclined to let it lie. Judging the conversation to be dead and the communication to be abortive. However, keeping pace with the disappearance of the words—and as the friction is heightened—something else arises in our attempts to deal with unfamiliar forms of communication. Language makes its way out to the edge of what we know it as but reveals itself in other new ways, compelling us to lead ourselves and the voice into territory that we are not accustomed to.

A considerable part of this communication is found in gestures, facial expressions, and other visible, physical movements. The extent to which we use our bodies to communicate, and the ways in which we do this, are culturally determined. The paralinguistic index does not take this into account but deals exclusively with that facet of communication that we use our voices to carry further.

When it comes to using the index, the voice and sounds are therefore essential. As we move out into the territory where we no longer rest on our acquired languages and our usual ways of communicating, and instead move out towards what the artist and researcher, Imogen Stidworthy calls rub-up, the voice provides involuntary information.2 According to philosopher, Adriana Cavarero, the voice reveals itself in all its uniqueness, and it is by this means that we show ourselves to one another. The voice becomes an opening to the other, an invocation, and an invitation for you to show yourself to me.

The index is also a digitised typography, a font, which can be installed on a computer and used on a keyboard. I developed this font so that I could more easily use the characters in my transcription work but also for the purpose of turning it into a freely available tool for others who might find some meaning in producing a transcription of this communication that otherwise has not been available to them. I believe that the index can be a way of opening up a communication. The font is available to everyone, and it can be accessed and downloaded at the top of this page.

Application Methods

Through developing this body of work, I have been making use of conversations that I conduct in Danish as well as those in Italian, for which I have had an interpreter (my father) on hand. In their expression and their dynamics, the resulting transcriptions vary widely, and these differences depend wholly on whether I am transcribing the conversation as a text, in its entirety, or “live” as sound.

When I transcribe in Italian, I enjoy a certain advantage in the sense that I do not know or understand all the words. That is to say, I am listening automatically for recognisable markers in the communication that I can grab hold of. However, the paralinguistic index also reveals itself to be incomplete; this is something I was actually counting on, inasmuch as I am missing characters—or perhaps it is rather that the characters’ individual categories are too narrow. Italian has a completely different kind of play with vowels and consonants, and especially with the interviewee with whom I have been working. Here, one could use the symbol l from the index, indicating the prolonging of an utterance, or one could create a more generalising kind of symbol to indicate that a certain vowel or consonant is being fiddled with. However, in a purely communicative sense, the vowels and consonants in the Italian language make their appearances in markedly different ways, and an extra rolling r feels incredibly far away from a soft double consonant—also in relation to how they are produced by the body.

One can use the index to transcribe and present a recording “live”; this is to be understood in the sense that the transcription is related to the audio file’s timeline. This method is independent of an already existing text or language, and therefore it is also independent of communicating in the same language. The characters are inserted, or they are marked, on the timeline in the moment they occur. One can, in much the same way, carry out the method for the transcription process intuitively and spontaneously by making the requisite markings while simultaneously listening to the recorded sound file. The obvious way to present and to work with this would be in a video-editing program, which visually renders the sound’s oscillations as an aid and which allows symbols to be inserted right into the image. The result is that the characters turn up on the screen at the same time that the paralinguistic language emerges in the sound, simulating subtitles on TV.

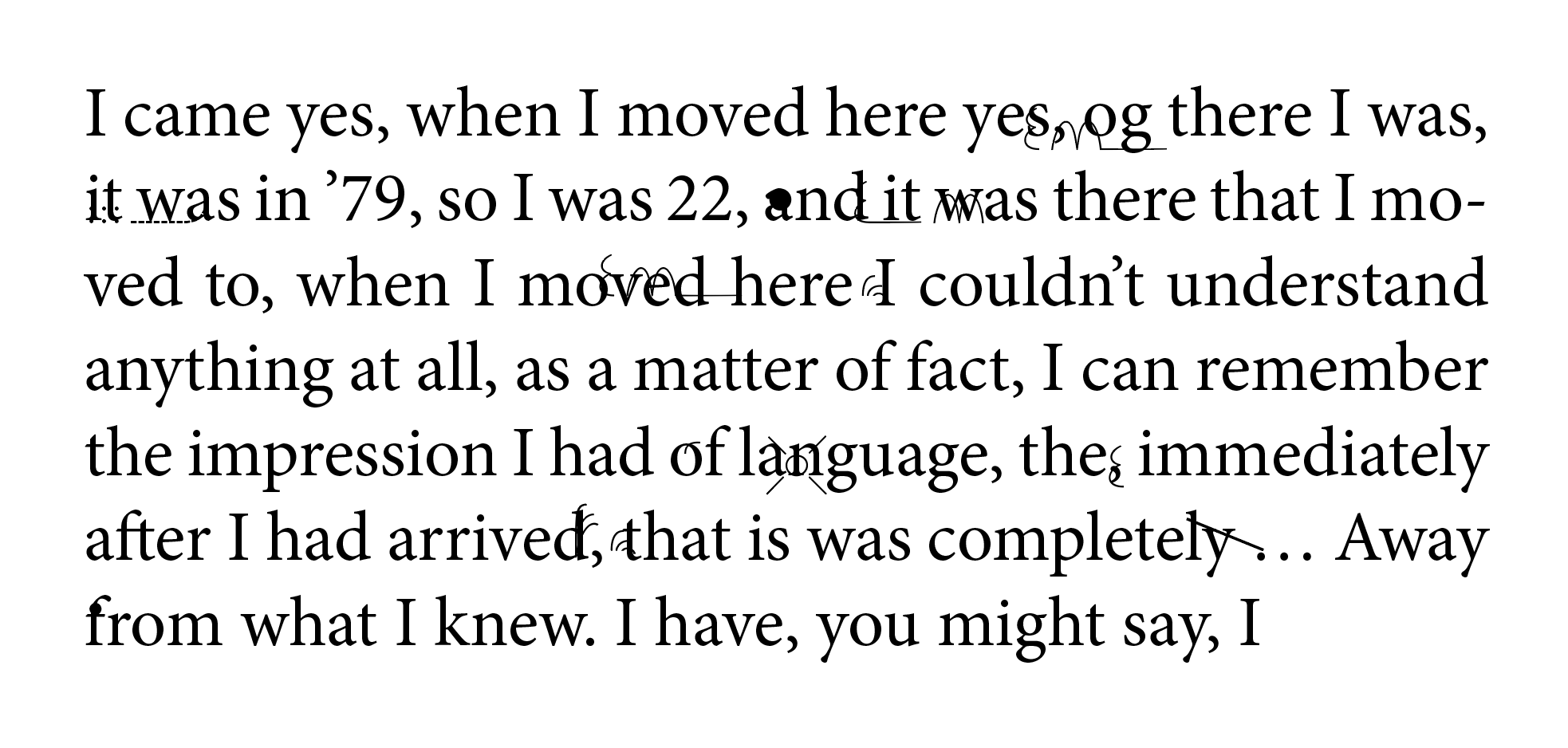

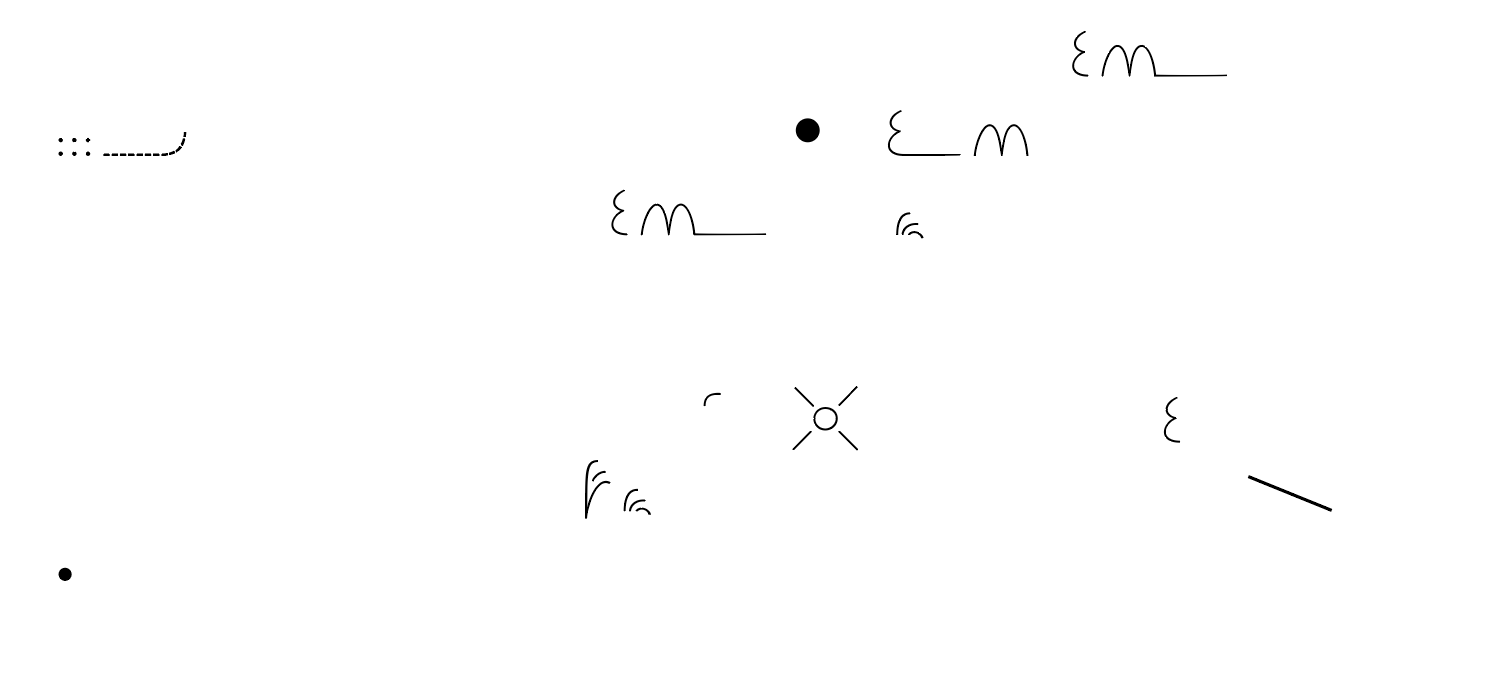

It’s also possible to use the index with the original transcribed text and its related sound file. Here, the original text is transcribed on top of it at the same time that it’s being listened to. The blank spaces already found in transcription become filled in. Moreover, a number of symbols get added in the form of exhalations and inhalations along with those that lie on top of the existing words. Here, the translation is consequently related to the format that we know and normally relate ourselves to: a reading direction moving from left to right, and from top to bottom—the same time-related issue. The transcriber is then free to retain the original text and allow the symbols to abound on top of the existing text, as an addition or an extension of the already prevailing language. Or the transcriber can dispose of the original text and focus instead on making the new transcription of the paralinguistic language. The result thereby becomes a configuration of the recognisable layout of a page, albeit with unknown symbols that move their way down over the page, in what I experience as a random and free movement. I also read the paralinguistic transcription as a graphic score, as a script that can be interpreted in the same way that the American poet, Susan Howe’s voice, in the most wonderful mode, reads and interprets her own text works. My graphic scores emerge something like this:

︎

3

31 Mirene Arsanios, Notes on Mother Tongues: Colonialism, Class, and Giving What You Don’t Have (New York: Ugly Duckling Presse, 2020)

2 Imogen Stidworthy, ”Voicing on the Borders of Language” (PhD diss., Lund University, 2020)

3 Example of a transcription of a recorded conversation using the Paralingual Index. In this example, on the left side, the paralingual transcription is displayed on top of the original. On the right side, we see the paralingual transcription alone.